It was more than a decade in the making, but when the North Carolina History Center at Tryon Palace opened in New Bern in October 2010, everyone agreed hands down that it was well worth the wait. The Construction Professionals Network of North Carolina was among its admirers and presented the construction team with its 2011 Star Award for new construction over $20 million. The Star Awards seek to honor the most outstanding new construction project in the state and are selected on the merits, owner satisfaction and challenges faced.

“It was an extremely complicated project, so we were very comfortable with the timeline,” observes Tryon Palace Director Kay Williams. “Our goal was to create a quality building that will be standing – and treasured – 100 years from now. And we wanted a 21stcentury design that did not overwhelm the landscape or the Palace, but rather complemented them.”

The well-planned and meticulously executed 60,000-square-foot structure is an engineering marvel and an architectural masterpiece. It was designed by Raleigh-based BJAC in collaboration with Quinn Evans Architects, with offices in Washington, DC. Clancy & Theys Construction Company of Raleigh was the construction manager at-risk who oversaw the work of 34 subcontractors. As many as 175 workers were on-site at any given time.

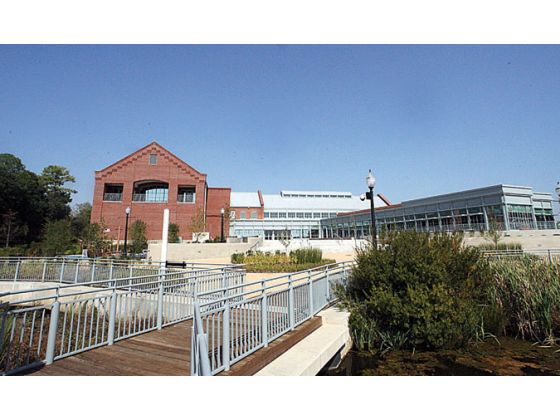

The two-story North Carolina History Center reflects five distinct historical industrial architectural styles and draws on themes of the waterfront’s earlier uses: a boat yard and warehouse. Brick masonry pavilions are linked with contemporary-style glass and metal-clad galleries. These varying looks are tied together through the consistent use of materials such as metal roofing, brick, precast and siding, all of which serve to blend historic and new elements harmoniously within the evolving context of downtown New Bern.

The Center is also on the transformational edge of changing how visitors experience museums. Says Jennifer Amster, BJAC’s principal in-charge, “Going to a museum is no longer a passive experience – it’s about engaging visitors in new ways. By juxtaposing virtual and hands-on experience-based learning, we accomplished something new: visitors experience history—it’s actually a reinvention and redefinition of what defines a history museum.”

Tryon Palace, a reconstructed, historically-accurate 1760s governor’s mansion, was first opened to visitors in 1959. At 25,000 square feet, it is only about 40% the size of the new North Carolina History Center. BJAC was hired in 1999 to create a master plan for the six-acre site, which was completed in 2001. It was put on the shelf for another four years until design was reinitiated, and ground was broken in 2008. The timing of the museum’s opening was particularly appropriate – New Bern celebrated its 300th anniversary in 2010.

Dreams for the Center actually date back to 1997 when the State of North Carolina purchased the old Barbour Boat Works site adjacent to the palace grounds so Tryon Palace could have a visitor center.

While their ambitions for the Center grew, Tryon Palace was faced with an environmental challenge. The shipyard was a federally-designated Super Fund site highly contaminated with asbestos, PCBs and other toxic chemicals. An abandoned gasification plant across the street also contributed to the polluted soil. It took more than five years to remediate the site.

The museum’s campus sits on the riverfront, where the soil is soft. Nearby structures were beginning to sink. To prevent these issues, the building sits on 600 pilings, some as deep as 100 feet. “It’s built to Florida hurricane standards,” Williams says.

The Tryon Palace board was committed to sustainability and to minimizing the building’s water and energy consumption. “We see ourselves as stewards of historic landscapes, and we also want to invest in the future,” Williams explains. The Center will be the first LEED-certified museum in the North Carolina and the first LEED building in New Bern.

To accomplish this vision – and meet LEED Silver requirements – BJAC architects used out-of-the-box thinking. The master plan created wetlands on the site to treat storm water from 50 surrounding acres. This took years, not months, to make happen. Underneath the Center’s courtyard is a 35,000-gallon cistern that catches runoff from the facility’s roof; much of which is used to irrigate the grounds. This water reclamation system rests on the pilings and had to be built at the same time as the building’s foundation.

“There were complex challenges all over the place,” comments David Kay, Clancy & Theys’ senior project manager.

Williams praises Clancy & Theys for its commitment to sustainable building practices. For example, she notes that company staffers made public presentations about the building’s construction to educate residents about sustainability issues.

Williams’ praise extends to all of construction team’s work. “Clancy & Theys did an incredible job and went out of their way to be creative – it was a once-in-a-lifetime project.”

As a partially-funded state project, budget considerations played a big part in every decision. “Money was always in the back of our minds,” Kay says. “Working within the budget was a group effort – we were continually brainstorming and bouncing value-engineering ideas off each other.”

That approach was indicative of the entire process, Amster observes. “Good clients make for great projects, and Tryon Palace had a strong vision of what they wanted the museum to be. The collaboration between the construction and design teams was unusually strong. We all worked very cohesively together.”

In addition to Clancy & Theys building responsibilities, the company also oversaw coordination of the exhibit construction. This was a new experience for the company. The Center’s building design – handled by William Drewer of Quinn Evans, who died unexpectedly in January 2010 — was driven by the exhibits, rather than fitting exhibits into a space that was already designed. Power and load requirements, lighting, cabling and data access were all integral parts of the planning, design and construction stages.

Collaboration extended beyond the design and construction teams working with the owner and started before the first line of the schematic was put to paper. Williams says the museum met with various stakeholders before design began, including residential neighbors, permitting officials and environmental activists. Nearby homeowners were communicated with regularly during construction, including door-to-door notifications when construction became noisy.

“Time spent effectively on the front end meant we didn’t have to stop and solve problems in the middle of construction,” Williams says. “And we kept communicating the vision at every step of the way”